“Today’s supply and investment plans are geared to a world of more gradual, insufficient action on climate change… They are not ready to support accelerated energy transitions.”

– IEA

At a time when official inflation figures are coming down and the Fed seems to be winding up its rate hiking cycle, many commentators are still putting inflation purely down to specific events – Covid lockdowns and the war in Ukraine – and therefore expect the CPI to gradually return to the central banks’ 2% target.

The structural issues behind inflation – the ballooning national debts and underinvestment in commodity production – remain unsolved but largely ignored by the mainstream.

A façade of Fed control here will only stimulate economic activity – and demand – and then I suspect we’re in for Inflation Spike II over the next couple of years, and structurally higher inflation for the next decade.

We have some commentators and asset managers claiming that both inflation will return to a 2% target and that we will have a rapid transition to a sustainable economy at the same time. One wonders whether these people have considered where the minerals will come from.

The inflationary impact of the energy transition is widely under-appreciated. This huge demand boost only gets satiated by pushing up prices high enough to spur a capex cycle the likes of which the world has never seen.

Energy transition minerals, as part of the wider energy theme, could present one of the best investment opportunities of our generation.

Contents

Performance

Transition minerals – what’s required

Supply constraints

Stock picks

Portfolio

Final thoughts

Performance

YTD: -4%

2022: +1%

2021: +10%

2020: +49%

2019: +51%

Transition minerals – what’s required

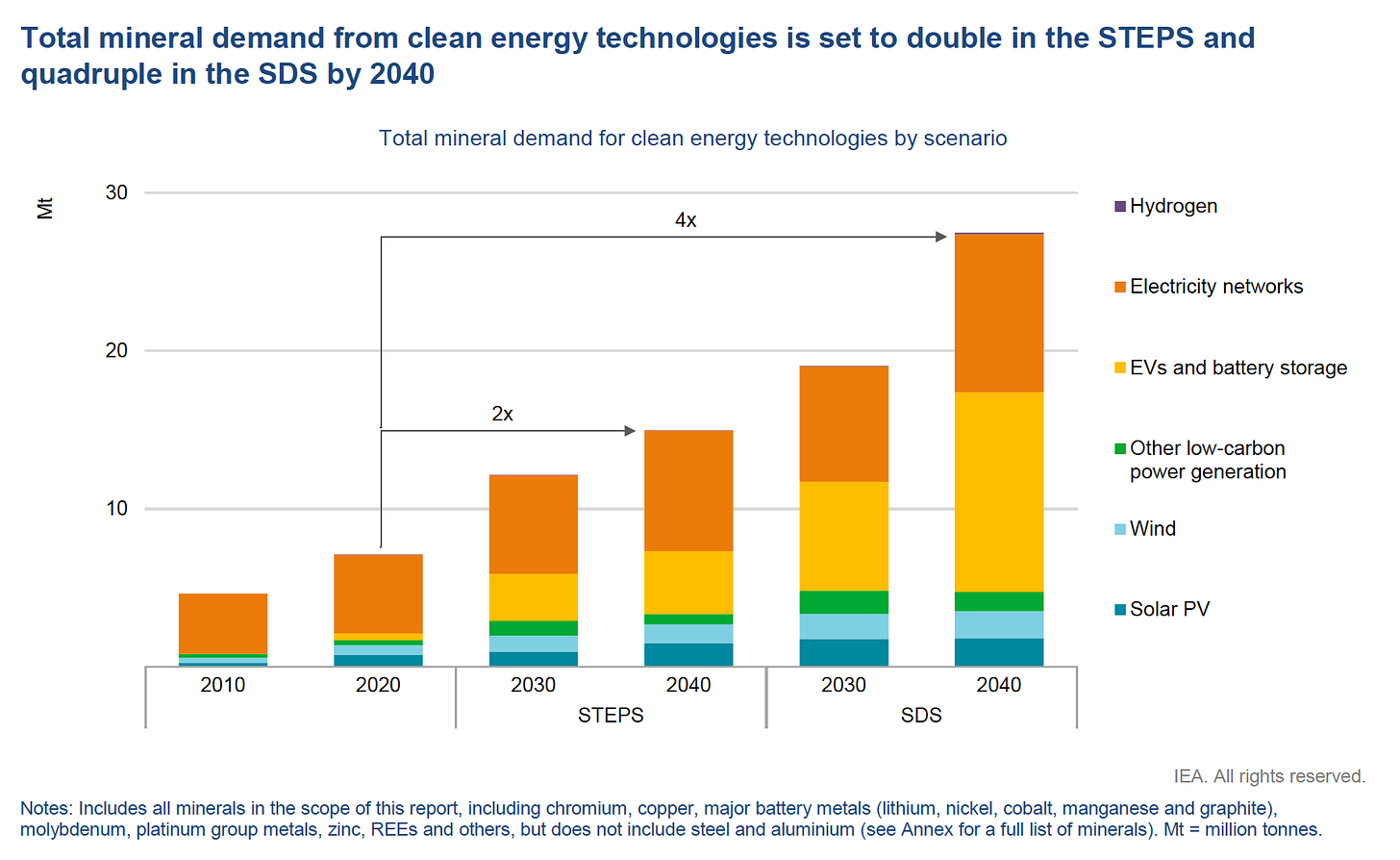

In its detailed study, The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions, the IEA illustrates the growth in supply required: a doubling of clean energy supply for critical minerals between 2020 and 2040 just to meet the IEA’s Stated Policy Scenario (STEPS), and four times the supply to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, under the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS).

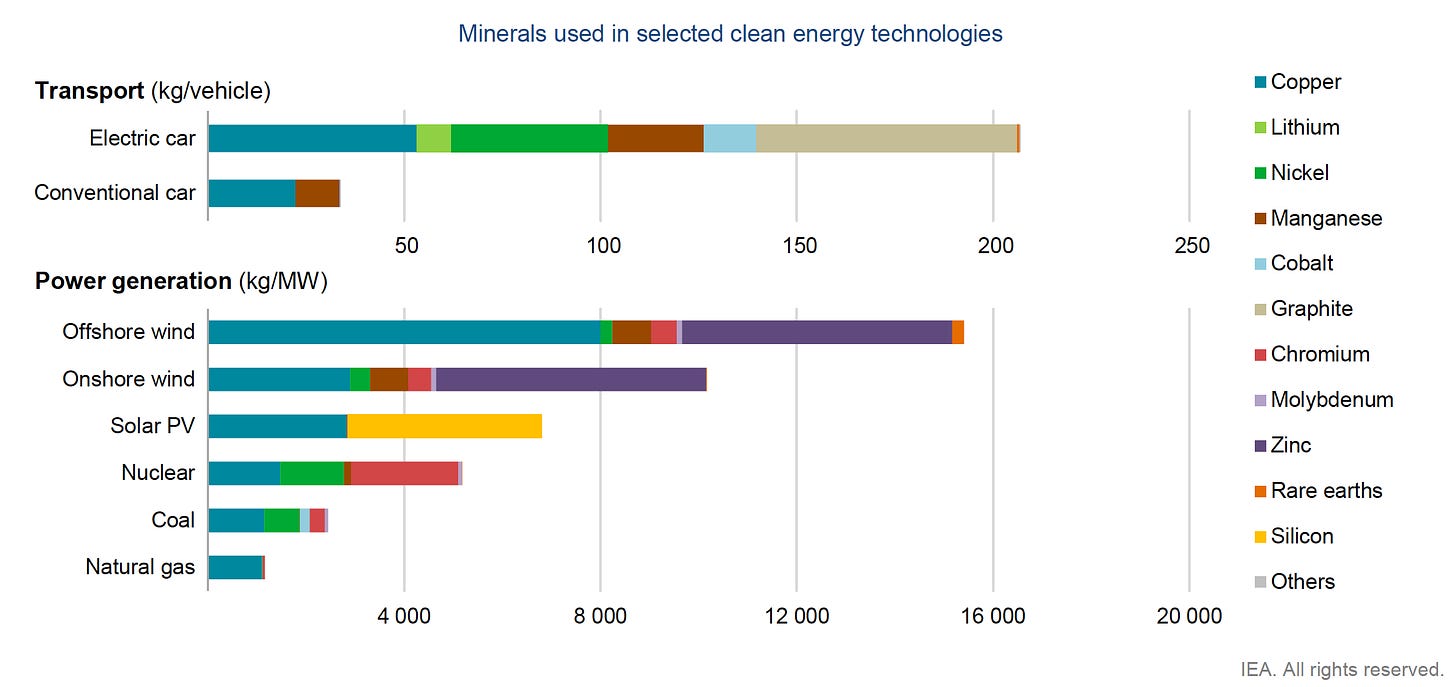

Electric vehicles typically require 6-7x the mineral inputs of an internal combustion engine car. Wind turbines use 7-10x the minerals of a gas plant, and enormous quantities of steel and concrete that are not included in the below chart.

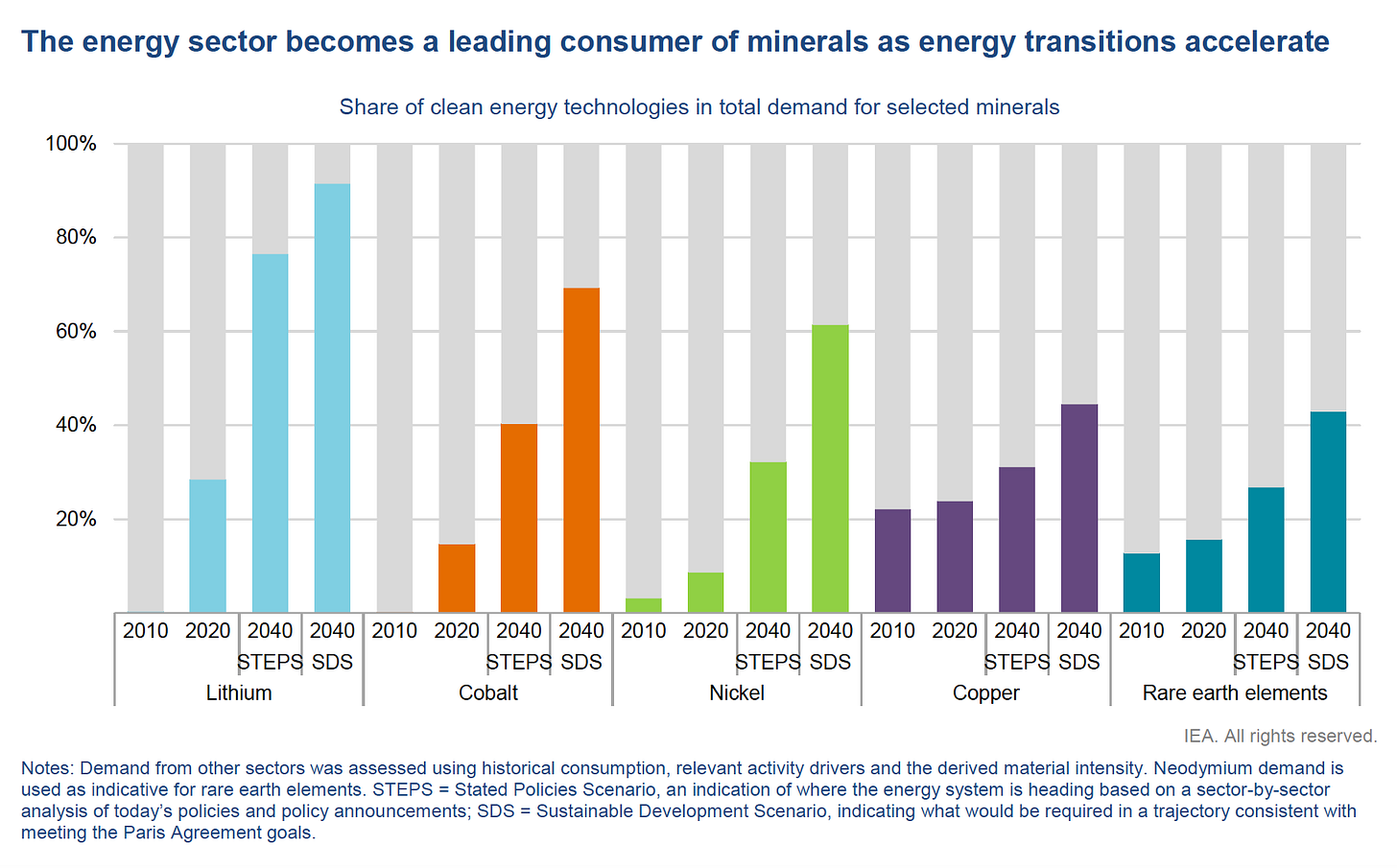

The share of the energy sector as a consumer of minerals is predicted to increase dramatically, particularly for lithium, cobalt and nickel.

Updating national power grids to integrate more dispersed power sources will involve a huge amount of copper, up to a doubling by 2040 according to the IEA study.

In the SDS scenario, lithium demand grows a staggering 42 times, followed by graphite, cobalt and nickel at around 20 times.

The quantity of metals required to meet the Paris Agreement goals for 2040 are so high that, still with little movement on capex, the goals look increasingly unlikely. It’s mindboggling that so many people have not yet realised that, as the years go by without the capex response to mine the commodities, the Paris goals are very much not happening as things stand, let alone net zero.

Supply constraints

“…in a scenario consistent with climate goals, expected supply from existing mines and projects under construction is estimated to meet only half of projected lithium and cobalt requirements and 80% of copper needs by 2030.” – IEA

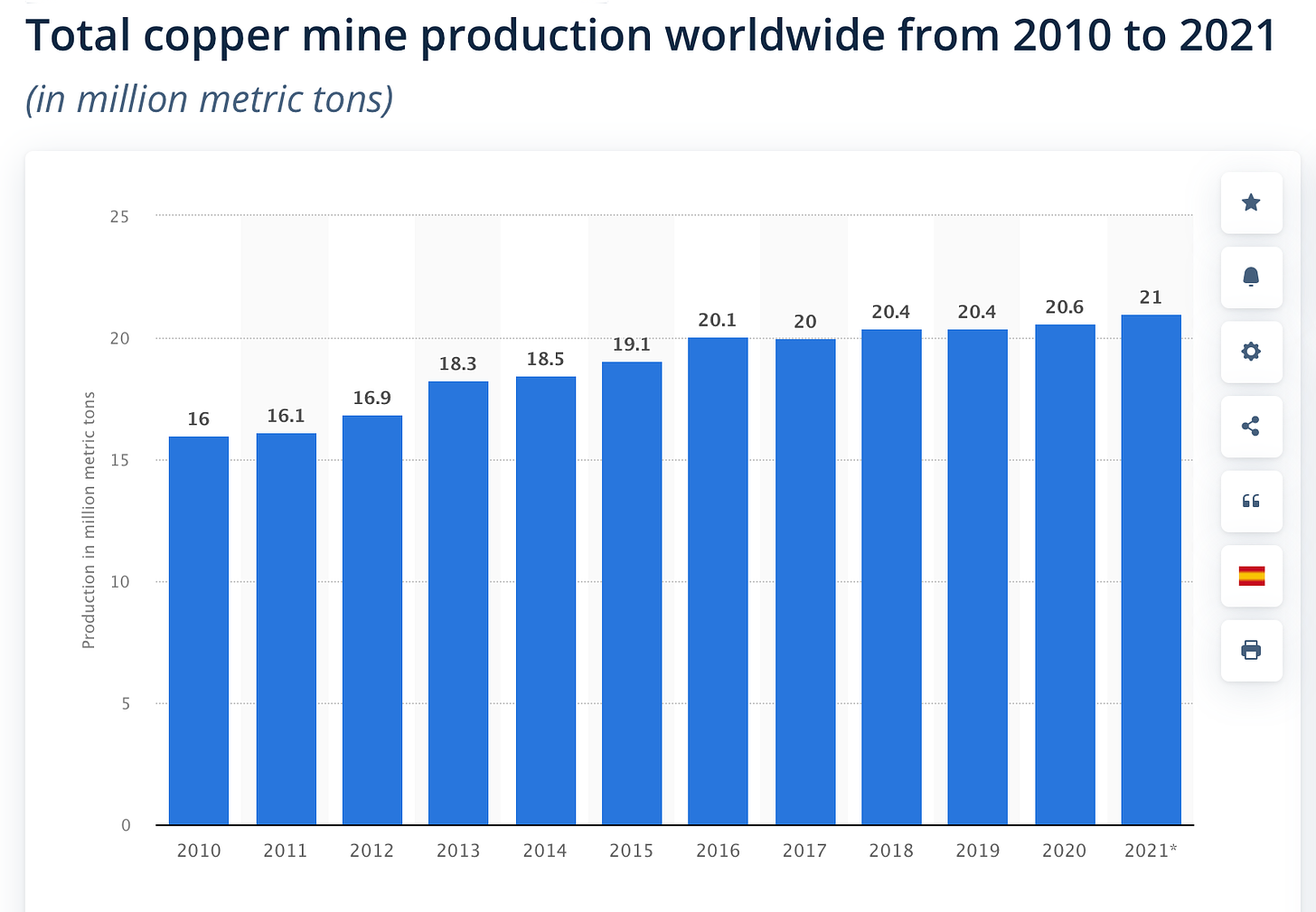

Global copper production has only increased by 5% in a five-year period, between 2016 and 2021.

Mineral producers are struggling with declining resource quality. Ore quality has continued to fall across a range of commodities as the highest grade ore available is typically mined first. The average copper ore in Chile has declined by 30% over the last 15 years. Extracting from lower grade ores requires more energy and is more expensive.

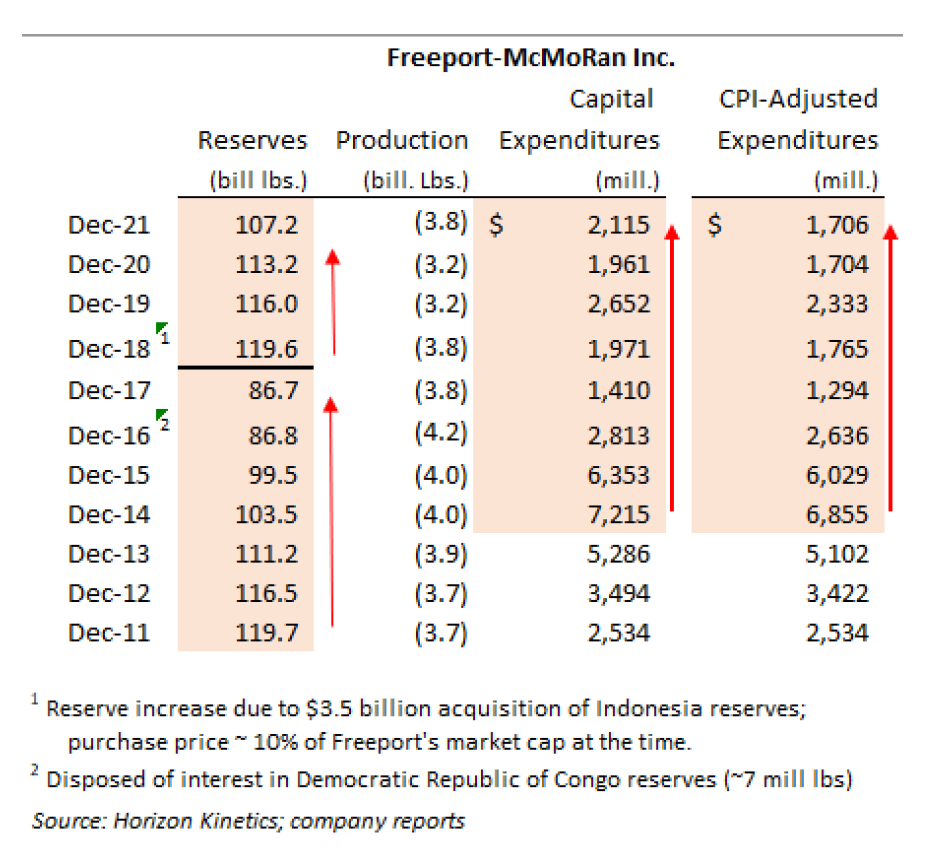

Investment advisor Horizon Kinetics illustrates that leading copper miner Freeport-McMoRan’s reserves have been in decline for a decade. Production has remained flat and capital expenditures have declined, but this has come at the cost of reserve depletion.

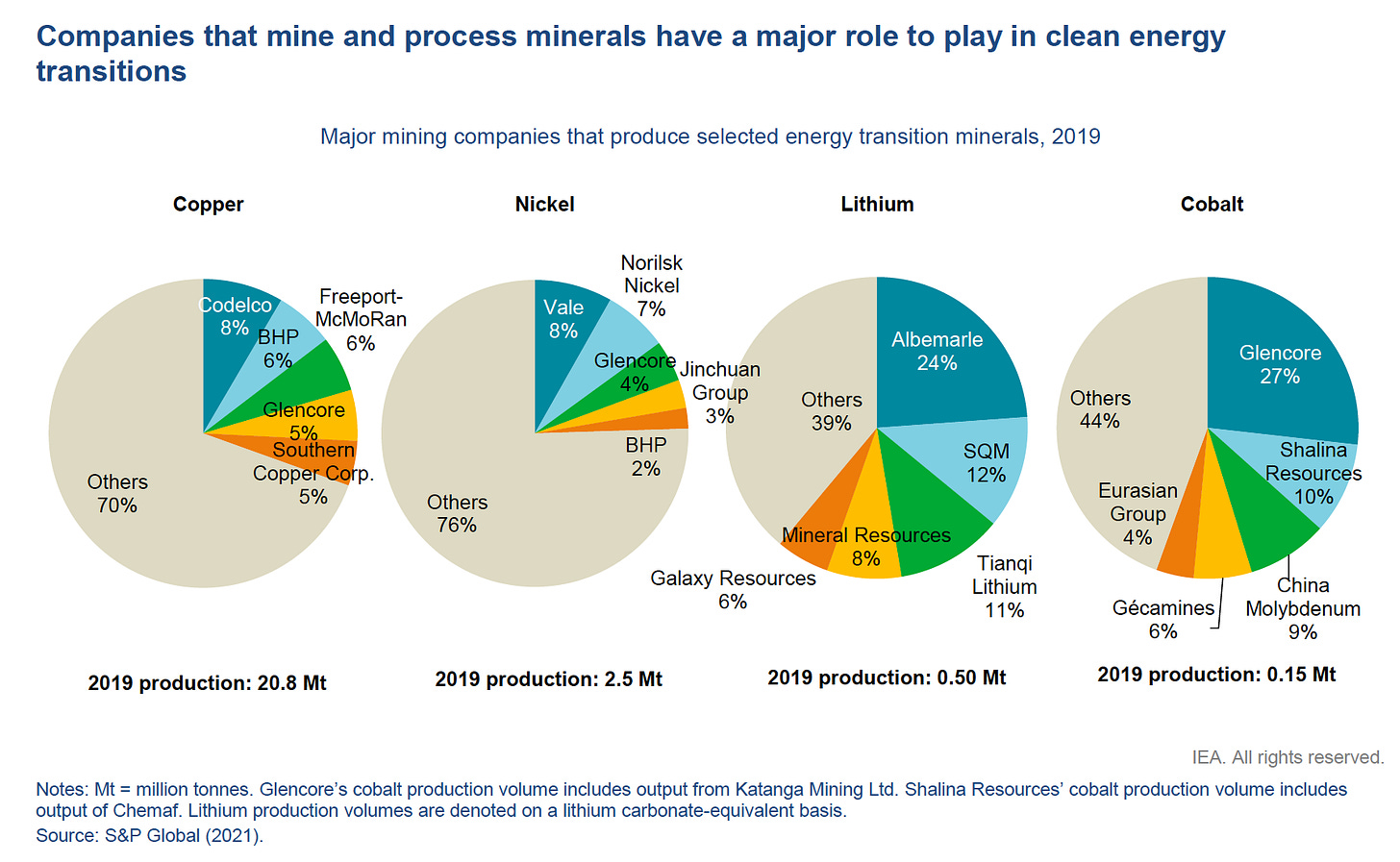

Another supply-side issue is the geographical concentration of transition minerals production, which leaves supply chains vulnerable to country-specific risks.

The top three producing nations control over three quarters of global output for lithium, cobalt and rare earth elements (REEs). South Africa and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are responsible for around 70% of the production of platinum and cobalt respectively. China accounts for well over half of global REE production. For copper and nickel, around half of global supply is concentrated in the top three producing countries.

Further, many of the key mineral producing regions are exposed to drought (copper and lithium have a high water requirement), flooding or heat, which all pose risks to reliable supplies.

On top of these limitations, various stakeholders, including investors and customers, are increasingly exerting pressure on miners to source and produce minerals responsibly and sustainably, which can both constrain output and limit or delay the development of new projects.

In the past, when demand for commodities has risen more than supply, it has been higher prices that ultimately spurred capital investment and supply responses. Mineral projects have very long lead times – the IEA reports that it has taken an average of 16 years to move from discovery to first production of mining projects – and so, if companies wait to commit capital until supply deficits emerge, a supply shortfall could cause high prices for many, many years.

High mineral prices could negate any cost savings over time expected due to increased battery and other technological efficiency, and therefore could have a major impact on the speed of the transition, which in turn would temper demand. However, there is also quite a lot of demand inelasticity for minerals when, for example, a doubling of the price of lithium or nickel would increase the price of a battery by only around 6%, according to the IEA study.

Indeed, there is room for transition minerals to maintain higher prices amid the multi-decade demand boost called the energy transition. Ultimately, the infrastructure only gets built, and the demand only gets satiated, by pushing up prices high enough to spur a capex cycle the likes of which the world has never seen.

Investing in energy transition minerals, as part of the wider energy scarcity theme, could be a generational opportunity.

Stock picks

Glencore (GLEN.L) – copper, nickel, cobalt, zinc

Glencore is an excellent choice for broad exposure to transition minerals – it has a finger in all the pies apart from lithium.

It is one of the top five producers of both copper and nickel, and the largest cobalt producer. It has almost as much copper production as Freeport-McMoRan and a market cap in the same ballpark, although copper only accounts for around 20% of Glencore’s EBITDA.

The company’s 2023 free cash flow (FCF) is projected at $14.6bn. The market cap is $85bn and net debt $2bn, so the enterprise value is priced at a reasonable 6x 2023 FCF.

With thermal coal making up over half the EBITDA, it doesn’t get the multiple of a pureplay copper producer. However, without the coal segment, the rest of the business is still only priced at 7x EBITDA, or perhaps 15x FCF.

The coal segment can be very lucrative in the near term, funding dividends, share buybacks, M&A and capex on the transition minerals. Longer term, as the thermal coal segment is gradually wound down, the transition minerals should shine.

Total shareholder returns during 2022 were $8.5bn, including dividends and buybacks (~10% distribution), based on 2021 earnings. 2022 should be a record year as EBITDA in the first half of the year alone was $18.9bn – and 2023 capital returns will be based on 2022 results.

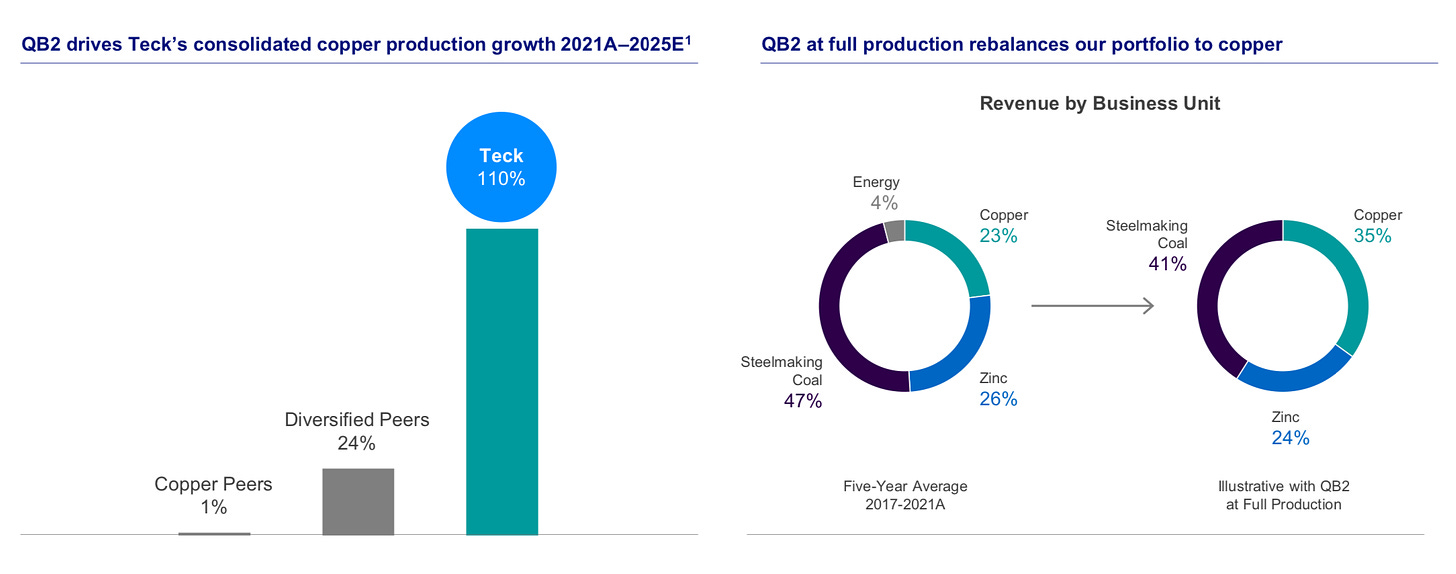

Teck Resources (TECK-B.TO) – copper, zinc, coking coal

Teck Resources is a Canadian mining company with segments in steelmaking coal, zinc and copper. Steelmaking coal and zinc are both essential transition materials – steel is one of the most essential materials across clean energy, and zinc is required in enormous quantities for building wind turbines. It is copper, however, that Teck is rebalancing its portfolio towards.

With its Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 project (QB2), it is targeting 110% growth in copper production from 2021 to 2025 to increase copper to 35% of total revenue. The company claims to have the potential to add 5x 2021’s copper production in the very long term, including a target to 3x 2021’s production by 2029.

The market cap is at C$21.9bn and net debt was C$5.3bn at the end of Q3, resulting in an enterprise value of ~C$27bn. The company could make around C$4bn in FCF at current commodity prices, putting the enterprise value at around 7x FCF. It seems a good deal for exposure to a rare case: a rapidly growing large-cap copper producer.

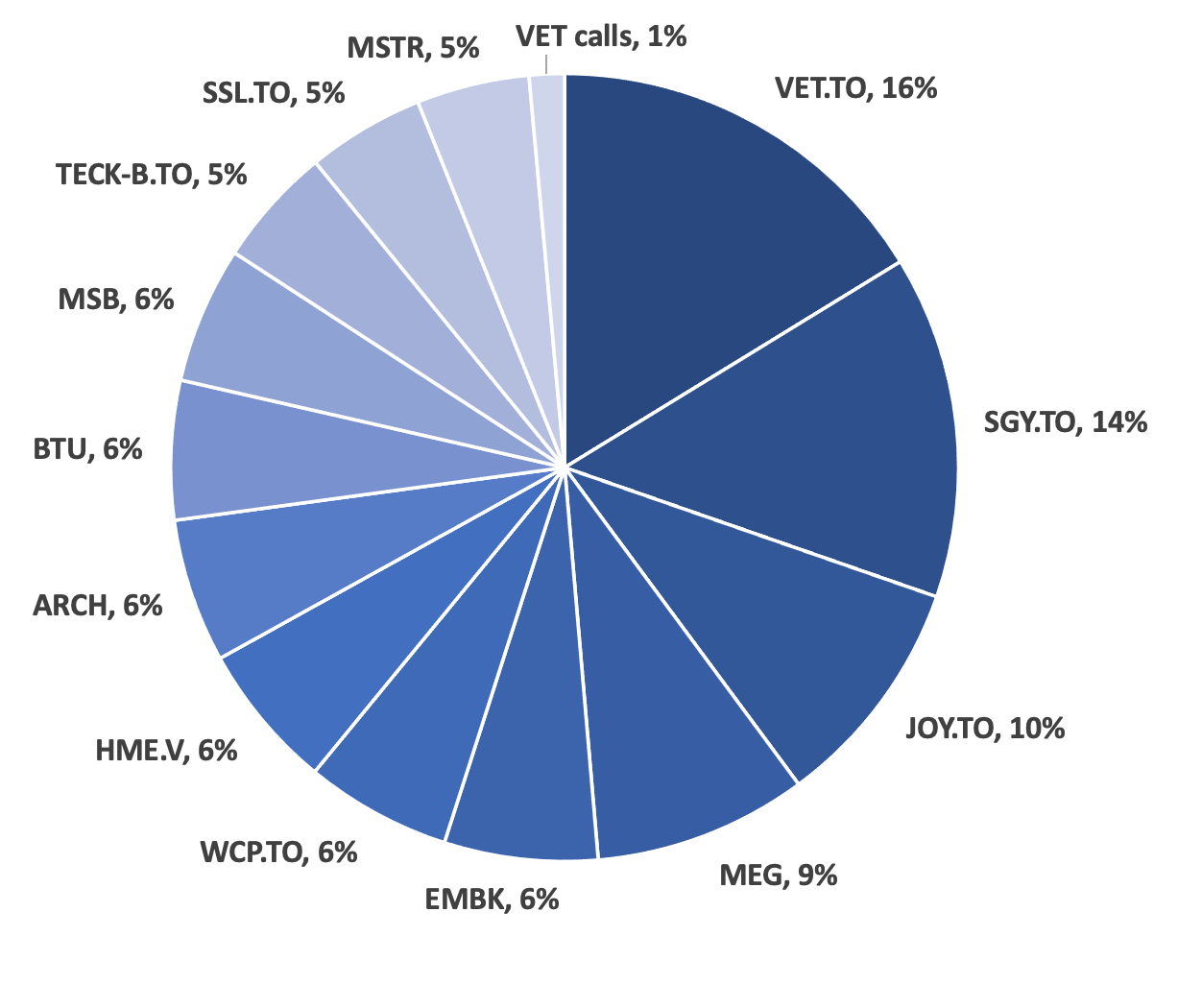

Portfolio

In January, I trimmed several energy positions in order to add some exposure to other commodities. I trimmed VET.TO, SGY.TO, MEG.TO, WCP.TO, HME.V and ARCH.

I bought:

TECK-B.TO (copper, zinc, coking coal)

SSL.TO (gold, silver, copper)

MSB (iron ore)

BTU (coal)

MSTR (bitcoin)

I also plan to buy a position in Glencore.

A full-length write-up on an undervalued company will be sent out later in the month.

Final thoughts

We’re having renovation work done on the house and so we’re staying at an AirBNB for a couple of weeks. Only 25 minutes away from home, but it’s a change of scene. Waking up to this and working here is very peaceful!

With best wishes,

Timothy Lamb.

Written by Timothy Lamb

Blog: www.retailbull.co.uk

Twitter: @theretailbull

Disclosure:

The writer owns shares in TECK-B.TO at the time of writing. Please see the portfolio for full disclosure. I may initiate a position in GLEN.L.

Disclaimer:

This article is for informational purposes only, does not offer investment advice and does not recommend the purchase or sale of any security or investment product. Please see the full disclaimer on the About page.

Definitely has been a good idea to buy these two stocks during dips

## Glencore:

> The company’s 2023 free cash flow (FCF) is projected at $14.6bn.

They, unfortunately, did nothing close.

EBITDA was down 50% YoY to $17.1B

> $17.1 billion Adjusted EBITDA, down 50% year-on-year (y/y), primarily reflecting the rebalancing and normalisation of international energy trade flows, with coal and LNG, and to a lesser extent, oil prices materially declining

While still returning MORE value to shareholders - $10.1B compared to ~7.3B in 2022.

It's an interesting company