Dear subscriber,

Cracks are widening throughout the global financial system.

In the first issue of the newsletter since it has moved to Substack, I will be focusing on macro, and it will be a two-parter. Part 1 is on the global debt spiral and the search for sound money, and the second instalment will be on the European Energy Crisis.

The approach of the Buffett school of thought is to focus rather on the micro than the macro: on individual companies, about which we can know a great deal – versus focusing on everything, about which we can know nothing!

This idea today seems rather akin to putting up a tent in a hurricane!

There is a storm brewing which can’t be ignored. This understanding helps direct us to certain mis-priced companies and investments.

Contents

Performance

The debt spiral

Sovereign bonds: teetering on the edge

The search for sound money

Performance

YTD: +11%

2021: +10%

2020: +49%

2019: +51%

The debt spiral

Things are starting to unravel. Global bond markets and currencies are under great strain, with grave implications for everything from the affordability of servicing national debt to people’s ability to pay their mortgages.

The central problem is that countries around the world, including the US, have got themselves so overleveraged that they need very low interest rates to keep any hope alive of paying the interest on their national debt without resorting to more borrowing to do so.

With the supply constraints we have seen since the Covid recovery, combined with the massive stimulus during the pandemic, we now find ourselves with high inflation and the US raising interest rates in response.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts the debt to GDP ratio ballooning ever upwards. In their Budget and Economic Outlook, May 2022, they say:

“As deficits increase in most years after 2023 in CBO’s projections, debt steadily rises, reaching 110 percent of GDP in 2032—higher than it has ever been—and 185 percent of GDP in 2052.”

Ex hedge fund manager James Lavish illustrates beautifully how the current US interest expense is already under-funded, in his article, What's a Debt Spiral, and is the US already in one?:

Total tax revenue is an estimated $4.4 trillion. Interest expense is $400bn – but there is only $300bn available to pay it, creating a $100bn shortfall.

As the debt matures and needs to be replaced, it is replaced at higher interest rates.

If the interest on the debt was just 3.2% (below the current 10-year at 3.8%), the annual interest expense would be $1 trillion. The country would be bankrupt.

Therefore, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has to pivot from its hawkish monetary policy by lowering rates and resuming quantitative easing (QE). But long-term low rates and QE will cause more inflation further down the line from the growing money supply. When the CPI runs hot once more, it again has to raise rates and borrow at higher interest rates, adding to the unsustainable debt.

Even running the CPI deliberately hot with ‘QE infinity’ doesn’t solve the problem as investors, once understanding this is the policy, will demand higher yields to be compensated for loss of purchasing power.

Sovereign bond markets: teetering on the edge

The Fed’s rate rises are piling up straws onto the camel’s back of global currencies and bond markets. And many of them are in worse debt situations than the US.

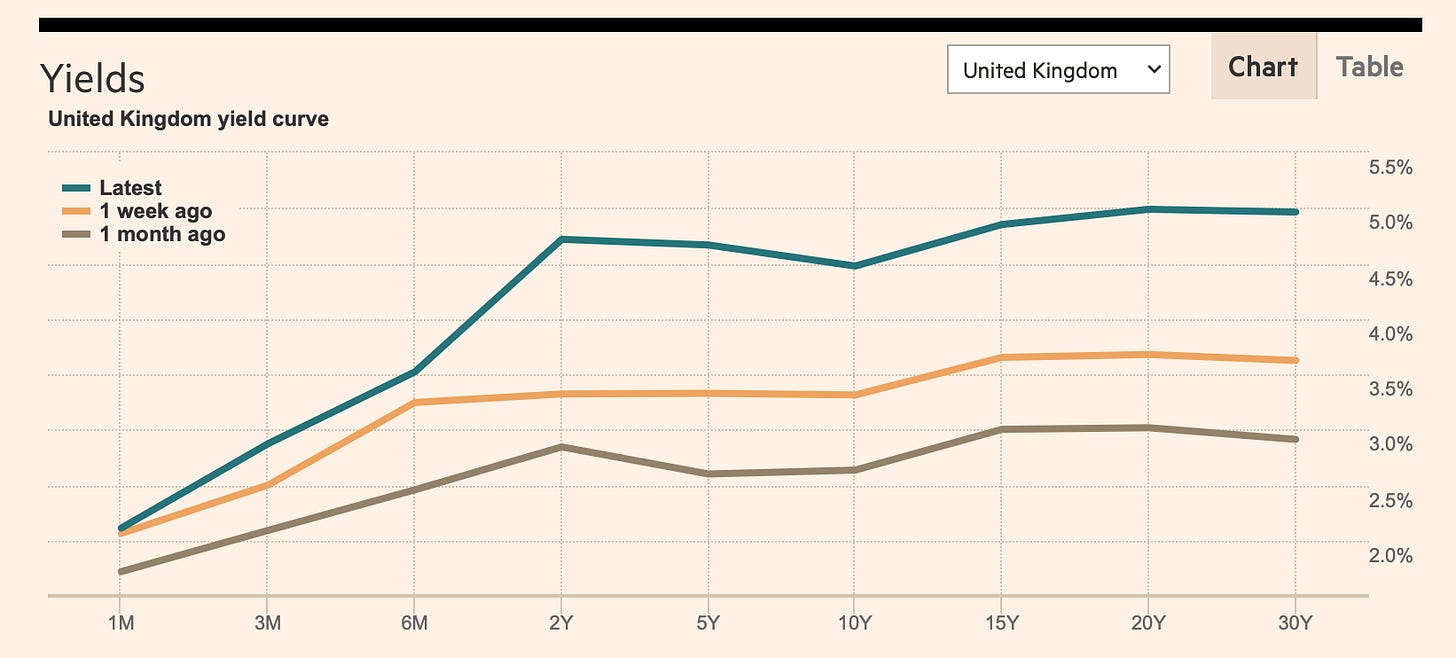

Following the UK government’s announcements of huge energy bailouts and tax cuts funded by borrowing – in a desperate attempt to stimulate GDP – the pound briefly fell to its lowest level ever against the dollar in September.

The government bond market (gilts) sold off in tandem to reflect the increased risk of the debt and the need for higher rates to prop up the currency. We then witnessed the beginning of a collapse of the gilt market as pension funds became forced sellers of gilts to meet margin calls.

The 30-year gilt yield rocketed from 3% at the end of August to over 5% during the last week of September. This weekly and monthly chart is something you might expect from an emerging market – not a G7 country.

The Bank of England stepped in and re-started QE, as a temporary measure, ostensibly to prevent margin calls and heavy losses for pension funds (Frances Coppola argues it was more likely to protect banks).

So, in the UK, we’re now doing QE into double-digit inflation.

Meanwhile, Japan is buying unlimited amounts of its own government bonds to peg the 10-year yield below 0.25% – it simply can’t afford higher rates at debt to GDP of 266%, the highest in the G7.

And the European Central Bank is buying billions of euros worth of Italian government bonds and those of other Southern European countries in a bid to control the yield spread between theirs and the German bund yield.

There are gaping cracks all over the world in the debt market. Without a pivot from the Fed, one of these straws could break the back of the financial system.

Perhaps the Fed pivots – if it gets enough warning. But there are no good options here. Whichever way we turn, whether tax cuts and fiscal stimulus (UK policy), austerity, higher interest rates or QE, it’s not clear how anything digs the world out of the debt spiral.

A global currency reset may still be a long way off but it looks like the only ultimate solution.

The search for sound money

A fiat currency has value because the government issuer says it does. It is backed by promises to pay, but ultimately promises to pay in paper. ‘Fiat’ means ‘by decree’, and fiat currency is the opposite of money backed by a physical asset such as gold, as used to be the case with the dollar and the pound.

Fiat is guaranteed to debase. There will be more creation of money from bank lending – commercial banks effectively create new money when they extend you a loan – and there will be more money printing in the form of QE.

If you have more units of currency in the economy, eventually the units get distributed and you have more units competing for a fixed quantity of good and services. Scarce goods go up in price as people bid for them. This results in inflation.

A ‘hard’ currency then is a medium of exchange and a store of value that is backed by a scarce asset.

Energy – such as oil and gas – is a much better store of value over a long period than fiat currencies. Oil, gas and coal are the building blocks of our entire modern civilisation and are universally needed. As opposed to fiat currencies, you can’t print natural gas (as Europe is unfortunately about to find out); you have to expend a lot of energy, money and effort to drill it out the ground.

The same is true of gold. The supply of gold increases slowly. However, with commodities, the supply growth is correlated to demand and therefore price. If the price goes through the roof, you can bet people will be digging more of it up – and this in turn balances the market.

Bitcoin is also backed by energy, the energy expended to ‘mine’ it. Bitcoin is energy that has been turned into a secure and finite money that can be stored safely by anyone, accessed with just a set of keywords and sent instantly peer to peer with no intermediaries.

As such, bitcoin is superior to both energy and gold as a medium of exchange and a store of value. In addition, no matter what the demand or the price are, the supply is completely fixed, making it arguably the hardest money ever created.

Energy producers, bitcoin and gold are three assets to consider to resist being sucked into the debt spiral.

Part two of the newsletter, on the European Energy Crisis, is coming soon.

Written by Timothy Lamb

Blog: www.retailbull.co.uk

Twitter: @theretailbull

Disclaimers:

This article is for informational purposes only, does not offer investment advice and does not recommend the purchase or sale of any security or investment product.

All the content is subject to copyright with all rights reserved. No permission is granted to copy, distribute or modify any text or logos. The content shall not be published, rewritten for broadcast or publication or redistributed without prior written permission from Timothy Lamb.

Those who access this information agree to the following:

While the material is often about investments, none of it is offered as investment advice. This means that neither the receipt nor the distribution of information through this website constitutes the formation of an investment advisory relationship, or any similar client relationship. The materials are not to be relied on for any purpose and are not investment, financial, legal, tax or other advice, recommendation or research.

The materials are for informational and educational purposes only. Educational articles are purely theoretical, with the purpose to enhance financial understanding and education, and members of the public are not advised to in practice follow any of the information provided.

No warranty is given with respect to the correctness of the information provided. Any projections or analysis should not be viewed as factual and should not be relied upon as an accurate prediction of future results.

All information and content on this newsletter is furnished without warranty of any kind, express or implied. This newsletter may contain performance and other data. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Timothy Lamb will not assume any liability for any loss or damage of any kind arising, whether direct or indirect, caused by the use of any part of the information provided. Timothy Lamb does not warrant that the content is accurate, reliable or correct, or that any defects or errors will be corrected.

Good work Tim, good luck building this out, you deserve it.